Rambo.

There's a lot of baggage attached to the two syllables of that famously gruff name. You could almost forget that David Morrell thus named the troubled protagonist of his debut novel after French writer Rimbaud.

In England, there's excess baggage: following the

Hungerford massacre in 1987, tabloid sensationalism forged a link in the public consciousness between fictional character Rambo and real-life killer Michael Ryan.

All four of the Rambo films have had their share of critical brickbats:

‘First Blood’ was drubbed for toning down Morrell’s novel (Rambo injures his pursuers during the manhunt, whereas in the book he kills them; Morrell’s ending is decidedly more apocalyptic).

‘Rambo: First Blood Part II’

‘Rambo: First Blood Part II’ and

‘Rambo III’ were written off as right-wing military fantasias; and the latest installment, simply yet iconically titled

‘Rambo’, has taken a kicking for, variously, having Rambo backed up by a group of mercenaries instead of being a one-man army (which he never was: in episodes two and three his ass is saved by indigenous freedom fighters), lacking the guidance of Colonel Trautman (well, d’uh, Richard Crenna died in 2003 - no-one else could fill the role), and simplifying the Burmese militia/Karen rebels conflict into sadistic, murderous, raping tyrants vs. fearless resistance fighters (well, yeah, tyrants generally are murderous bastards, that’s why they're tyrants, and resistance fighters, because they take their lives in their hands by defying entire armies, pretty much deserve the epithet ‘fearless’).

Now, I’m not saying that I espouse violence, nor can I argue that the sight of one muscle-rippled individual hefting the kind of hardware it would normally take a crane to lift, and using said weaponry to cut swathes through infinitely superior numbers, isn't vaguely ridiculous ...

But.

There’s more to the Rambo films (even, in a clutching-at-straws kind of way, episode three) than they’re generally given credit for.

Do I sound like an apologist? Not so. This time last month, I’d seen only ‘First Blood’ once, studiously avoided the next two installments and hadn’t really given much thought to the latest film. Then two considered, intelligent reviews - on

Moon in the Gutter and

Out 1 - peaked my interest. I bought a ticket for ‘Rambo’ and took my seat. The lights dimmed, the facile adverts and generic trailers came and went. The film started. Ninety minutes later, I emerged, blinking, into the light. I felt like I’d been grabbed by the throat, wrenched from my seat and thrust head-first into the mud-caked, blood-drenched, visceral, brutal, confusing horror of conflict. I can’t think of another film this side of

‘Cross of Iron’ that has rubbed the audience's nose so unapologetically in the sickening actuality of do-or-die warfare.

Brandon Colvin, at Out 1, compares ‘Rambo’ to

‘The Bourne Ultimatum’ as a hyper-kinetic example of the kind of cinema that tears away the spatial restrictions of the screen its projected on and forces the viewer the engage with it on the most immediate level. I tip my hat to a man, a better writer on film than I could ever hope to be, for describing so intensely and intelligently why ‘Rambo’ isn’t just a film you watch but one you experience. (Sir, there's a pint with your name on it if you're ever in Nottingham, England.)

Jeremy Richey at Moon in the Gutter, in a turn of phrase that would have had me jump to my feet and applaud had I not been sneakily reading his review at work, describes ‘Rambo’ as "the kind of film

‘Saving Private Ryan’ would have been if Steven Spielberg had any real kind of film-making balls, which he doesn’t". (Sir, there's a pint with your name on it, too.)

Two days after I’d seen ‘Rambo’, I walked into HMV and bought the box set of episodes one to three. I watched them in sequence over the last two nights. My immediate thoughts:

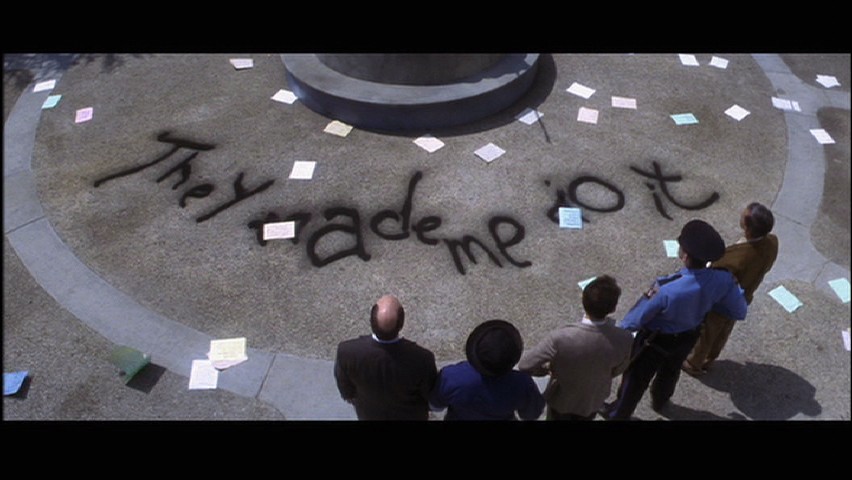

‘First Blood’ was as pacy as I'd remembered it, Ted Kotcheff’s direction as clinically efficient as his protagonist’s fieldcraft. Vietnam vet John Rambo (Sylvester Stallone), unable to hold down a regular job, walks/hitch-hikes across the States, fetching up at the rural home of a former platoon member. When his widow coldly informs Rambo that he died of cancer, blaming his exposure to Agent Orange, Rambo is forced to accept the depressing fact that he’s the last survivor of his outfit. With nowhere to go and his future uncertain, he wanders from town to town. In the ironically named Hope, hippie-hating sheriff Will Teasle (Brian Dennehy) mistakes him for a beatnik, picks him up and drives him out of town. Snubbed, defiant, Rambo refuses to leave. Teasle arrests him for vagrancy and hauls him down the cells, where sadistic Deputy Sheriff Art Gault (Jack Starrett) gives him hell.

But as the tag-line has it, hell is what he calls home. Rambo fights his way out of the police station and heads for the woods outside of town. Teasle and his men give chase. Rambo bests them, leaving them alive but comprehensively whupped. His former commanding officer Colonel Trautman (Crenna) turns up and exhorts Teasle to pull out. Teasle (a medal displayed in his office suggests he’s served in the military) continues the manhunt, enlisting local militia. Rambo, hiding in a disused mine, survives a grenade launcher attack by the skin of his teeth and responds by bringing the war to Hope.

So, ‘First Blood’ in a nutshell: soldier returns home from war, is rejected by society (“they called me baby-killer”), victimised by authority and reverts to what the army trained him to be purely because he’s given no other choice. Powerful stuff for an eighty-nine minute thriller whose pace never flags.

Fast forward a couple of years and ‘Rambo: First Blood Part II’ finds Rambo breaking rocks in a high-security prison, having been incarcerated after he desists from killing Teasle at Trautman’s behest. If Trautman curtailed the narrative in the first film, he instigates it here and in part three. Informed that participation in a mission to establish the whereabouts of American POWs still MIA in Vietnam could lead to a presidential pardon, Rambo accepts and is parachuted into still-hostile territory with only the barest survival equipment. He makes contact with local freedom fighters, but meets betrayal before he reaches his objective.

Fast forward a couple of years and ‘Rambo: First Blood Part II’ finds Rambo breaking rocks in a high-security prison, having been incarcerated after he desists from killing Teasle at Trautman’s behest. If Trautman curtailed the narrative in the first film, he instigates it here and in part three. Informed that participation in a mission to establish the whereabouts of American POWs still MIA in Vietnam could lead to a presidential pardon, Rambo accepts and is parachuted into still-hostile territory with only the barest survival equipment. He makes contact with local freedom fighters, but meets betrayal before he reaches his objective.

Trautman’s superior officer, Murdock (Charles Napier), tasked to investigate the credence of MIA myths (with the politically-demanded result that he will find no evidence), pulls the plug on the mission when Rambo locates American captives in a prison camp. Left to capture and torture, Rambo only escapes thanks to the intervention of a woman, Co Bao (Julia Nickson) – the hero of a supposedly right-wing military fantasia rescued by a woman! - and takes it upon himself not only to liberate his fellow countrymen but settle the score with Murdock.

So: ‘First Blood Part II’ in a nutshell: loose cannon palmed off with a suicide mission and (almost) fucked over by an administration more concerned with plausible deniability than duty to the members of their armed forces lost in action. And there was me believing the critics, thinking that it was just a few reels of macho bullshit.

Fast forward a few more years and ‘Rambo III’ emerges as slavishly beholden to its predecessor’s template: a rescue mission (this time it’s Trautman who's been captured), the assitance of a rebel army (Afghans resisting the Soviets), the Red Menace instead of the VC, torture scenes involving electrocution. Maybe I watched parts two and three too close together, but it's hard to shake the impression that ‘Rambo III’ is Rambo-by-the-numbers.

However:

It moves fast. It doesn’t pretend to be anything it isn’t. It doesn’t glamorise American intervention. If anything, all of the Rambo films depict American intervention abroad as an arrogant inevitability, one that regular people will carry the can for (even if, like Rambo, those regular people have been re-programmed by the army as killing machines) and struggle to adjust to in civilian life, while the top brass in both the military and the administration wash their hands.

So: ‘Rambo III’ in a nutshell: politics is shag-wank and only friendship counts. (Sorry, I’m still not getting this right-wing military fantasia thing.)

Still, there's no denying that ‘Rambo III’ is the weakest installment. Which makes the re-emergence of the character, twenty years later, so much more impressive.

‘Rambo’ starts with newsreel footage of killings and torture in Burma, then delivers a prologue in which Burmese soldiers force a group of villagers to race through a paddy field into which they’ve tossed explosive devices and place bets on which of them get blown to bits. Rambo himself is living down-river in Thailand, operating a river boat and catching snakes. The old soldier has found a sort-of peace in the jungle, even if his dreams are ridden with flashbacks.

It doesn’t last. A group of Christian missionaries engage him to take them into Burma where they can minister to the oppressed natives. (Their brief interaction with a village community has them dole out Bibles and band-aids.) Rambo at first refuses, but is persuaded against his better judgement by the idealistic Sarah (Julie Benz).

When the missionaries are captured by the Burmese military, Rambo is again approached, this time by the Reverend Marsh (Ken Howard). The missionaries’ pastor, he responds to their plight by hiring a band of mercenaries. This is certainly the film’s most nihilistic concept: the clandestine government-backed military intervention of parts two and three replaced by right-wing Christian intervention. When the Bibles don’t work, break out the bullets.

Stallone, directing and co-writing, takes the action scenes to a new level. He also gives himself very little dialogue. There’s no moralising, no proselytising. Rambo does what he does. What he was trained to do. He is what his country turned him into. He can no more escape who he is than Clint Eastwood’s William Munny in

‘Unforgiven’.

The last scene echoes the opening shot of ‘First Blood’, lending an apposite circularity to things. There is a sense of hard-earned closure, reminding us that there is – always was – a human side to one of American cinema’s most enduring anti-heroes.

With a tip of hat to Antagony & Ecstasy, I'm declaring it Week of the Dead here on The Agitation of the Mind, looking at George A Romero's five-film cycle of zombie movies ...

With a tip of hat to Antagony & Ecstasy, I'm declaring it Week of the Dead here on The Agitation of the Mind, looking at George A Romero's five-film cycle of zombie movies ...

‘Rambo: First Blood Part II’

‘Rambo: First Blood Part II’

‘The Isle’

‘The Isle’ 'Runaway Train'

'Runaway Train'