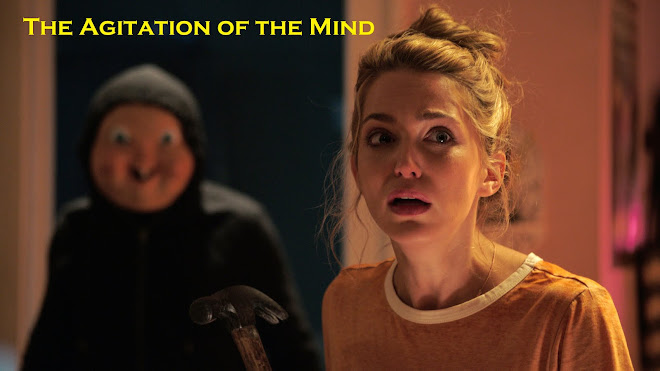

Tuesday, August 15, 2017

A Ghost Story

Just over halfway through David Lowery’s ‘A Ghost Story’ – that is to say after fifty minutes or so of minimal dialogue and the communication of ideas and emotions via imagery, music and deliberately slow pacing – there’s a party scene in which a completely random character delivers a five-minute monologue on the passing of time, the inevitability of death, the impulse to leave something behind and the nature of what endures in the name of humankind and why and whether this enduring is, in and of itself, inherently meaningful.

A five-minute scene, in other words, in which writer-director Lowery finds it necessary, for some bewildering reason, to have a not particularly charismatic actor stodgily verbalise everything the film has communicated thus far in a beautiful, poignant, hypnotically compelling and quintessentially non-verbal manner. It’s an annoying scene – as inelegant conceptually as it is unnecessary intellectually – and if Lowery were to take ‘A Ghost Story’ back into the editing room and snip it out he would immediately transfigure a very very good film into an outright masterpiece.

‘A Ghost Story’ concerns itself, essentially, with two characters although plenty of other people drift through the film. The fact that we never really get to know any of these other people is a purposeful aesthetic decision. Their lives are almost on fast forward, so quickly do they enter the film, inhabit a very specific place for a brief period, then move on. The lives of our main characters, however … well, that’s where the film finds what I might otherwise describe as its heart or soul, but a better description for ‘A Ghost Story’ would be its memory and its terrible sense of endlessness.

Our main characters are called only C (Casey Affleck) and M (Rooney Mara). C is a musician and an introvert. He clings onto a ramshackle house that M wants to move out of, claiming it has “history” (“not as much as you’d think,” she shoots back in a line that comes loaded, by the time she delivers it, with bitter irony), while M despairs of his lackadaisical attitude to life and tendency to hedge decision-making and responsibility. Still, what they have together seems to be the real deal – certainly if M’s grief after C dies in a car accident is anything to by. That wasn’t a spoiler, by the way.

M says goodbye to C’s mortal remains as he lies on a mortuary gurney. She pulls a white sheet back over him before she leaves. Returning home, it takes her a lot longer to say goodbye. M – or at least M’s ghost – rises from the gurney and makes a slow, defeated journey to the house they shared. Where he remains.

The first brilliant, beautiful thing that Lowery achieves is to have a man wearing a sheet with eyeholes cut into it as his ghost and it actually come across as heartbreakingly sad rather than utterly ridiculous or camp. Later, when M sees a fellow ghost in a neighbouring house, this other ghost’s sheet is patterned with flowers. It took me a moment or two: M died on a morgue trolley, this other spirit died at home under a patterned bed sheet. The attempt at communication between these remnants, and the abrupt departure of the latter when she (I strongly got the impression of the feminine though I’m not sure why or how) realises no-one she knew is going to return, will also break your heart.

The film’s notorious pie-eating scene – which is already coming to wrongly define ‘A Ghost Story’ – isn’t quite as poignant, but it says a lot about grief, survivor’s guilt and how it’s a bad idea to shoulder the pain of bereavement alone. Like everything that ‘A Ghost Story’ does – which is to say, everything single frame of it bar the lousy party scene – the communication is purely visual, slowly paced and forces the viewer into observing events from the ghost’s perspective. Not his literal POV, I hasten to add (the ghost is often in the same shot as other characters), but his perspective. The difference is crucial.

Lowery uses extended takes that recall Tarkovsky, while the look of the film is reminiscent of David Lynch’s small town Americana. The Tarkovsky touchstone is the more important. What Lowery achieves – miraculously, given that slender 92 minute running time – is to document the passage of time: fast for the various residents who inhabit C and M’s house after M finally packs up and leaves to start a new life; slow, painfully slow, for M in the immediate aftermath of C’s death; and functionally endless for C.

At some point after the party scene (have I mentioned how much I dislike the party scene?), Lowery throws the mother of all curveballs and poses the question: what happens when even a ghost tires of (un)life? How he answers that question is something I can imagine frustrating the hell out of a lot of people. At least one writer on film, whose opinions I hold as damn close to gospel, outright hates the direction ‘A Ghost Story’ takes in its last third. Personally, and with an eye discreetly turned to one specific temporal cheat, I found Lowery’s approach daring, provocative and philosophical. This would be a good moment, however, to acknowledge how important Daniel Hart’s score is vouchsafing Lowery’s overall vision. Hart’s soundtrack is a thing of beauty.

With the exception of that one damned scene, ‘A Ghost Story’ is as close to perfection as any film I’ve seen on the big screen this year has come. It is the most serious and mature discourse on the nature of love that you’re likely to see without there being subtitles at the bottom of the screen. It is the most affecting enquiry into death, memory and the nature of what remains that has been produced this decade. Its cinematography, performances and music (did I mention how much I love Daniel Hart’s score?) synergise to beautiful effect.

That fucking party scene. It comes stumbling into a movie that should have been a perfect ten and knocks it down a whole half a point.

Sunday, August 06, 2017

Valerian and the City of a Thousand Planets

So maybe we should just call it ‘Laureline and the Wet Lettuce Leaf’. Or, in ‘Friends’ stylee, ‘The Old Where a Gamine Catwalk Model Gives a Better Performance Than Clive Owen, Ethan Hawke or Herbie Hancock’. Or, in abject frustration that it seems to be heading towards being a flop, ‘The Luc Besson Sci-Fi Opus That’s Actually Better Than The Fifth Element and Fuck the Haters’. Or given how deliriously action-packed, joyously colourful and exuberantly imagined it is, ‘The Curiously Overlooked Summer Tentpole Release That’s a Fuckton More Entertaining Than Anything Marvel Have Tossed in Our Direction For Ages’.

Personally, and for the purposes of this review, I’m going with ‘Laureline: The Movie’. After a handful of nothing roles in unremarkable productions (‘Anna Karenina’, ‘The Face of an Angel’), a likeable turn in indie film ‘Paper Towns’ and being utterly wasted in the cluster fuck that was ‘Suicide Squad’, Delevingne grabs the role of Laureline with both hands and reinvents herself as the kind of sexy, sassy heroine who demands the camera’s unconditional worship. On this showing alone, I’d put her up there with the bona fide icons of Hollywood’s golden age. So, at the risk of Mrs Agitation consigning me to the doghouse, here’s a raised glass to Cara Delevingne, the Rita Hayworth or Ava Gardner of the Instagram generation.

*ceases typing … takes cold shower*

Where was I? Oh, yes. Luc Besson’s

I’m not even going to bother synopsising the plot. Besson overcomplicates it to allow for more genre tropes and more world-building. This is a movie whose visuals are the raison d’être and the narrative exists to move Valerian and Laureline from one location, one alien race, one production design orgasm to another. This is no bad thing: ‘Laureline: The Movie’ is the most visually gorgeous and extravagantly imagined work Besson has ever put his name to; it is, at one and the same time, a big-hearted homage to a certain era of sci-fi, and an expression of Besson’s credentials as auteur.

Narrative as a justification for moving an audience around a filmic chessboard, pausing here and there to deliver the kind of set piece that exists purely to demonstrate its own bravura, is a tag you can hang everyone from Hitchcock to Nolan by way of Clouzot, Frankenheimer, Friedkin and Tarantino, not to mention everyone who ever directed a giallo. Which is to say that most of the criticisms levelled against ‘Laureline: The Movie’ are total bollocks weighed against the pantheon of accepted classics. So you’re hating on Besson’s latest for the very same reasons that you unironically love ‘Barbarella’ as a camp delight? Yeah, whatever.

‘Valerian and the City of a Thousand Planets’ has two problems. The first is DeHaan – a likeable enough actor elsewhere on his CV but wrong for the role of Valerian in the way that John Inman would be wrong for a biopic of Bendigo or Dwayne Johnson as Charles Hawtry. The second is Rihanna, making the jump from shit pop singer to shit actress. To mitigate Rihanna’s performance, her intro is cannily staged to resemble a music video, thereby establishing a pop culture rationale for her character. No such excuse exists for DeHaan. The only reason any fucking scene he’s foregrounded in or line of dialogue he delivers works is because of Delevingne’s reaction shot. It’s as if, thirty seconds into the first day of shooting, Besson realised that she was his film-length insurance policy.

Beyond DeHaan and Rihanna, though, the film is just pure delight and spectacle from the stand-up-and-applaud brilliant opening sequence (played out to David Bowie) to the tense but mercifully not over-egged finale … and can I just say here, thank you thank you thank you for not dragging out the climactic setpiece to four times its feasible length the way every other fucking blockbuster of the last decade has.

Spectacle. Set design. World building. Brain-searingly gorgeous visuals. And on top of it all, Develingne in excelsis. Yes, I accept that I’m in something of a minority here. Maybe I’m in the weird yet privileged position of Luc Besson having spent hundreds of millions in making a film for me alone. If so, merci beaucoup; I owe you one.

Labels:

Cara Delevingne,

Clive Owen,

Dane DeHaan,

Luc Besson,

Rihanna

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)