Saturday, February 24, 2018

CROWHURST SEASON: The Two Voyages of Donald Crowhurst

To the best of my knowledge, the first documentary about the Golden Globe debacle was Colin Thomas’s ‘Donald Crowhurst – Sponsored for Heroism’ which aired on British TV in 1970 and is described in this excellent New Statesman article as “dour, scathing”. Having been unable to track down a copy or find it online, I found myself turning instead to ‘The Two Voyages of Donald Crowhurst’, an Arena documentary from 1994.

It’s a curious piece of work, this. The approach to the material is clinical to the point of detachment, with a voiceover delivered in the kind of vaguely condescending cut-glass English accent that suggests it was made the Fifties rather than the Nineties. With a running time just short of half an hour, it doesn’t allow itself the necessary breathing space to consider the subject matter in the depth it requires.

Particularly galling is the lack of attention paid to the other entrants in the race, and the whistlestop pace the documentary assumes in charting Crowhurst’s premeditated decision to post fictional updates of his journey, to the point at which madness overcomes him and he struggles with cosmic considerations of time, the universe and religion. ‘Two Voyages’ fails to communicate the sheer amount of time he spent in his own company, or to plumb the psychological fall-out of a man having to live with the impossible decision he made – a man alone, struggling to keep afloat an ill-prepared vessel, missing his family, terrified at the thought of financial ruination and reputational humiliation – for so long without being able to share the burden or make confession.

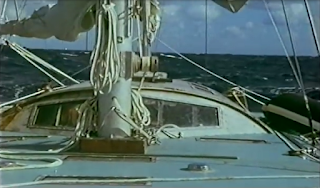

This aspect is especially frustrating since the documentary makes good use of Crowhurst’s own footage of the voyage. When he set out, the BBC gave him some sponsorship money, a cine-camera and a tape recorder, the intent being that he would keep an audio-visual log correlative to the written one and return with material that could be shaped into a documentary. The BBC probably had an entirely different conception of the documentary at that point in time!

‘Two Voyages’ is also effective in establishing the inherent contradictions between Crowhurst’s bright and breezy tape recordings and cine-cam footage, and the mental turmoil he was experiencing even as he continued to play the part that was expected of him. Had the documentary taken this schism as its starting point and really squared up to Crowhurst’s mental breakdown, it might have emerged as the definitive entry in the Crowhurst cycle. As it is, it’s the first piece of work that gives us Donald Crowhurst as a regular guy – right down to some audio of him blowing a melancholy tune on the mouth organ – with whom it’s all too easy to sympathise. But it only establishes that one aspect of Crowhurst, and does not (or cannot) get a fix on the Donald Crowhurst of those last weeks.

For a documentary that plays up duality in its very title, its inability to reconcile Crowhurst’s (perhaps self-created) public persona with the person he became as time wore on and his options ran out is bitterly ironic.

Sunday, February 18, 2018

CROWHURST SEASON: Horse Latitudes

‘Horse Latitudes’ is a TV movie made in 1975 with a running time of 41 minutes. For all its brevity, it takes a long hard run at including as many of the salient points of the Donald Crowhurst story as it possible: Crowhurst as amateur sailor, his boat as unready/untested, the mid-voyage dilemma, the invented log, Crowhurst’s psychological depletion, the concept of a cosmic being, the discovery of the unmanned vessel.

The weird thing about the film is that it does all of these things while almost wilfully fictionalising Crowhurst. The character presented to us by writer-director Peter Rowe is called Philip Stockton, he’s an expatriate Canadian living in England, he’s an entitled yacht club bore (albeit a more proficient sailor than the real Crowhurst), and he cooks up a scam to kill time in the calms of the South Atlantic (the horse latitudes of the title) then rejoin the race on the return leg before he’s even set sail.

Stockton is so evidently Donald Crowhurst in terms of the narrative context – ‘Horse Latitudes’ aired six years after Crowhurst’s unmanned Teignmouth Electron was found, and five after the publication of Nicholas Tomalin and Ron Hall’s much-lauded book on the subject, so the story would still have been very familiar to audience – and yet is completely unlike him in virtually every way the script could conjure.

For this reason – and also for the inclusion of a genuine weird animated sequence – ‘Horse Latitudes’ is an odd film to watch. There’s probably more to enjoy in it if one is unfamiliar with the story. Having seen ‘The Mercy’ on the big screen and ‘Deep Water’ on the small within the same 24-hour period in which I approached ‘Horse Latitudes’, I struggled with the latter’s fictionalisations. Why make him Canadian, apart from the fact that Peter Rowe is Canadian, as is Gordon Pinsent, the actor who plays Stockton? Why suggest that the deception was premeditated when the mid-voyage desperation that drove Crowhurst to his fateful decision is far more dramatic?

Both decisions weaken the film. Most subsequent approaches to the story – be they feature films or documentary works – address, to a greater or lesser degree, the very fact of Crowhurst’s Englishness. Not so much from a class perspective (the working class don’t, as Toad of Toad Hall would have put it, “mess about in boats”), but more a matter of Crowhurst fulfilling a national archetype: the underdog, the have-a-go hero, the armchair adventurer who decided to quit his armchair and live the adventure. Having Stockton as an ex-pat completely scotches these considerations; to the point, in fact, where Rowe struggles to identify Stockton’s motivation in joining the race. This may account for what seems like directorial impatience on Rowe’s part to get Stockton out to sea and have things start to go wrong for him. While ‘Horse Latitudes’ focuses on Stockton alone on the boat, Rowe is confident in his material. The land-locked scenes, however, are shoddy.

The idea of premeditation – that Stockton is nothing but a conman from the outset – does the most damage to the film. There is no sense of Stockton as anything more than a big-headed twat, a characterisation that effectively waves goodbye to the audience’s sympathy. It’s only the taut running time and Pinsent’s commanding performance that mitigate against utter loss of interest in the proceedings. Rowe’s implication that the falsified journey had always been Stockton’s back-up plan not only leeches tension at a crucial stage in the journey, but seems curiously un-sync’d, narratively and emotionally, with Stockton’s subsequent mental breakdown.

There are two ways to go as regards Crowhurst’s disappearance: accident or suicide. And while psychological derangement is a fit for both scenarios, the suicide angle plays more effectively in a dramatic context if it’s done with some degree of rationality: fear of being unmasked and bringing shame on his family; guilt that his fictitious achievements have spurred on a competitor to risk-taking and the loss of their vessel. Going mad and taking one’s life is very theatrical. Glumly and understatedly doing oneself in for lack of other options is very English. For all the romanticism and yearning for adventure and the lure of foreign climbs, there’s something about the English mindset that is almost claustrophobically narrow minded and more than half in love with failure. And for a country whose historical imperialism once saw it ruling half the globe, the island race mentality of foreignness as something that is bloody awful is deeply – psychologically – ingrained.

‘Horse Latitudes’ wants to have the madness in all its animated glory – I’m being sarcastic here: aesthetically, it makes your average Loony Tunes cartoon look like da Vinci – as well as the calm, almost pragmatic act of suicide. And it tries to reconcile these aspects without a single enquiry into the nature of Crowhurst’s national identity.

It’s one thing to fictionalise a true story – there may have been rights issues around Tomalin and Hall’s book; maybe Crowhurst’s family objected: I don’t know – but quite another for that fictionalisation to strip away the most crucial aspects of the story; the very underpinnings that define the story, that make it unique. Granted, there are some effective moments – Stockton’s meltdown at the difficulty of creating the log of a journey he hasn’t taken generates a real sense of the deception closing in on him – and Pinsent is never less than compelling. A more sympathetic script, an account of Stockton as a personality closer to Crowhurst, and Pinsent would have been so much better served. He’s the best thing about ‘Horse Latitudes’ and my cautious recommendation is entirely based on how well he sells some very difficult scenes in the last third. But – sweet lawd! – his director gave him a poisoned chalice.

Thursday, February 15, 2018

Crowhurst season on The Agitation of the Mind

A couple of days ago I took myself off to see ‘The Mercy’. I didn’t know much about the film or the true story it was based on, but I hadn’t been making use of my Cineworld unlimited card due to a recent spell of illness and I figured that anything starring Colin Firth and Rachel Weisz couldn’t be all bad.

‘The Mercy’ is a solid, well-crafted piece of film-making that benefits from Firth’s most engaged performance in probably a decade. It’s beautifully shot and the score by the late Jóhann Jóhannson is icily effective. But I came away thinking that it had shied away from the darker aspects of its subject. Almost as if director James Marsh had wanted to preserve an enigma, rather than meeting that enigma head-on and trying to get inside his protagonist’s head.

Nonetheless, the film managed to loop a hook into my mind. I drove home, poured a drink and spent an hour on the internet. I’d only vaguely known of Donald Crowhurst and the Golden Globe Race; I had no idea it was a subject that filmmakers had grappled with for over forty years. I noted that Nicholas Tomalin and Ron Hall’s book ‘The Strange Last Voyage of Donald Crowhurst’ had been reissued, and resolved to purchase a copy after payday. I made a list of the various films – biopics, documentaries, fictionalised treatments – based on the story. I found Louise Osmond and Jerry Rothwell’s 2006 feature-length documentary ‘Deep Water’ online and watched it. I turned it at way past midnight that evening (with work the next day) and dreamed of a waterlogged trimaran and the terrible loneliness of months spent at sea alone.

Crowhurst and the terrible outcome of his adventure was all I could think of next day at work. That evening, I found ‘Horse Latitudes’ online: an award-winning TV movie from 1975 that changed the principles’ names and took certain liberties in its presentation of Crowhurst, but remains an intriguing starting-point in terms of trying to distil Crowhurst’s bizarre story into a cinematic format.

Currently, I’m trying to track down several other movies and TV productions, and waiting for Simon Rumley’s ‘Crowhurst’ to get its theatrical release. Having ingested three Crowhurst features in 24 hours, the one thing I know for sure is that something about his story has gripped me, has made me want to drill down into it and look at all the angles. So, depending on how much material I can get my hands on, I’m declaring a Crowhurst season on The Agitation of the Mind – I’ll review everything I can get my hands on over the next couple of weeks.

Given that everything I’ll be writing about, no matter how different the aesthetic approach or the filmmakers’ agenda, will of necessity overlap in very specific respects, this article is perhaps the ideal time to set down the basic facts of the story so that I don’t have to rehash them ad nauseum.

In 1968, weekend sailor and inventor of navigational aids Donald Crowhurst threw his hat into the ring when the Sunday Times, keen to exploit Sir Francis Chichester’s recent round-the-world solo yachting triumph, threw out a challenge. Chichester had made one stop for major overhauls. The Sunday Times offered a hefty cash prize for anyone navigating the globe, alone, without stopping. There were in fact two prizes: one for the first sailor to complete the voyage, and one for the fastest. The start date deadline was 31 October – any later and certain stretches of the ocean might prove unnavigable.

The other competitors – including merchant navy veteran Robin Knox-Johnson; author, philosopher and adventurer Bernard Moitessier; and former submarine commander Bill King – were far more experienced than Crowhurst. Nonetheless, Crowhurst secured sponsorship from a local businessman, Stanley Best, and had a trimaran, the Teignmouth Electron, built to his own specifications. Crowhurst intended the vessel to be state-of-the-art and kitted out with a phalanx of his own safety and navigation devices; his intention was to market these gizmos on his return, benefiting from the publicity generated by the race.

To drum up said publicity, he hired crime reporter Rodney Hallworth as his press agent. It’s hard not to see Best and Hallworth as the villains of the piece. Though a millionaire, Best’s sponsorship of Crowhurst came with a caveat: that if Crowhurst dropped out or failed to complete the race, he would be legally obliged to buy back the trimaran from Best. With his house already remortgaged and his finances shoddy to begin with, Crowhurst had essentially staked everything on the Golden Globe. Hallworth went to town on the hyperbole in his, ahem, reports (embellishments might be a better word), creating a public expectation that Crowhurst would have been hard pressed to deliver on even if he were a more accomplished sailor and his boat actually ready at the point of departure.

The seeds of tragedy had been sown before he even departed English shores. With the 31st October looming and incredible pressure on him to set sail, it was clear that the Teignmouth Electron wasn’t ready. His self-designed safety equipment was installed but not functional; he kidded himself that he’d get them working whilst at sea. An ingenuous buoyancy device, intended to counter the fact that trimarans are more susceptible to capsizing than mono-hulled vessels, may as well have remained on the drawing board for all its functional capabilities.

After a false start, Crowhurst set sail on the last possible date. Progress was slow. Myriad problems with the Teignmouth Electron manifested. The hulls were prone to flooding and Crowhurst had to bail by hand. It was bad enough in relatively clement seas, but once he was round the Cape of Good Hope and into the “roaring forties” (a perilous stretch of ocean between the fortieth and fiftieth parallels) the ship would likely be swamped. Crowhurst gave himself 50/50 odds of actually surviving the trip.

Alone, ill-prepared, nowhere near experienced enough as a yachtsman, Crowhurst found himself in a galling dilemma: press on and risk both the ship and his own life, or turn back and face fiscal ruination and public humiliation as a failure. His solution was a huge gamble, even in pre-GPS 1968: he created a second log book in which he mapped out an entirely fictitious journey. He cabled progress updates to Hallworth claiming the doldrums were over and the Teignmouth Electron was achieving the kind of speeds of which he’d always insisted she were capable. He knew that his phoney log wouldn’t stand up to tooth-comb scrutiny, so he intended to rejoin the race in last place and play the plucky underdog card. He’d be forfeiting the prize money for the fastest circumnavigation, but he’d be free of his obligations to Best and he could still milk the publicity to the benefit of his business.

Only he’d reckoned without how hard a solo non-stop round-the-world yacht trip is, even for experience sailors. Robin Knox-Johnson, in a display of good-natured championship, was the first to complete the journey, but he’d taken his time in doing so. The £5000 prize for the fastest entrant (that’s about £100,000 adjusted for inflation) was still up for grabs. Except fewer and fewer contestants remained to grab it. Most dropped out, none more dramatically than Moitessier, who had channelled the solitude of the voyage into a philosophical sense of self-awareness. Knowing the he could never face the crowds and cameras and intrusions into his life and experience, Moitessier didn’t so much drop out of the race as simply ignore the finish line and sail round the world for a second time.

As Crowhurst communicated his false bearings, mainly telegraphically as he knew his radio signals wouldn’t bear out his claimed positions, Hallworth spun them into a narrative of underdog heroism, derring-do and record-breaking speeds. Naturally, all of this got back to the other competitors. Nigel Tetley was looking set to follow Knox-Johnson into second place. Concerned that Crowhurst was gaining on him, he pushed his boat too hard in ill weather and only just avoided going down with it.

Crowhurst’s deception was entirely dependent on coming last. Nobody, he was convinced, would give his log more than a cursory glance. But the news of Tetley’s disaster left him in an impossible position: Knox-Johnson had finished, and he, Donald Crowhurst, was the only other yachtsman still in the race. The £5000 prize and all the attendant publicity – in other words, the almost inevitable uncovering of the deception – were all but guaranteed.

At this point, Crowhurst quit sailing the Teignmouth Electron and just drifted through the kelp-clogged expanse of the Sargasso Sea. He opened a third log and wrote a bizarre 25,000 word essay on cosmic beings, godlike perspectives and the nature of time. The final paragraphs are indicative of a man who has lost his mind.

Days later, the trimaran was spotted by a passing container ship. It was deserted. The log books fell into Hallworth’s hands and the story they told was front page news. Crowhurst’s body was never found. Knox-Johnson donated his prize money to Clare Crowhurst and her children.

It’s the abject claustrophobia of the story that’s got under my skin. The idea of someone in a confined space (made more confined by the vastness of the ocean around him) making a decision born of the lack of other viable options and then finding himself unable to reverse or untangle that decision never mind the consequences. Then there’s the enigma: did Crowhurst deliberately commit suicide, or did he slip from the vessel while the balance of mind was awry. Are the contents of his final log a spiritual epiphany or demented ravings?

The subject is rife for conjecture; a jumping off point for the creative imagination. In addition to at least two published books on the subject and the (pardon the pun) raft of features, be they big screen, small screen, fictionalised or documentary, there have been theatrical productions, art installations, poems, even an opera. Donald Crowhurst set out to become a hero; circumstances forced him to become a fraudster; the enigmatic pull of his story, and its lure for artists, finally made him a legend.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)